[FEATURE]

WHEN JUSTICE DELAYED BECOMES JUSTICE DENIED

By: Jassie Bagatela & Cassandra Manguiat

Remembering Maguindanao Massacre — an election-related massacre that received international condemnation and appeared to have been politically motivated, with fingers pointed at a strong local clan.

Timeline of justice

November 23, 2009. 58 individuals, including 32 media workers were ambushed and killed in Maguindanao while covering an intense political rivalry. Aside from being deemed as the worst case of election-related violence, it is also the deadliest attack against journalists in Philippine history.

A recall of the narrative tells us that armed men stopped a caravan at a checkpoint in Sitio Masalay, Barangay Salman, Ampatuan, Maguindanao, named after the strong Ampatuan clan. Majority of the 58 slain individuals were part of a convoy headed to the provincial capitol to file Esmael Mangudadatu’s certificate of candidacy for provincial governor.

President Rodrigo Duterte has directed the prosecution panel in the Maguindanao massacre case to ensure partial rulings for some of the suspects by the end of 2018, according to then presidential spokesman Harry Roque.

However, only five of 80 suspects have been convicted until this day.

Then, on September 13, 2018,Roque said he will ask President Rodrigo Duterte to meet with the case’s prosecutor panel due to the delays in the trial.

After almost ten years, the trial had come to an incomplete finish on July 17, 2019—as justice remained elusive to hold the powerful Ampatuan clan accountable for their crimes just to stay in power.

Journalist Reynaldo Momay Jr., who was not considered a victim of the crime and has disappeared since then, may still be buried somewhere in Maguindanao with some of the truth of that horrendous day.

With unwavering hopes after almost ten years of calling for justice, the court declares the massacre case to be submitted for decision on August 22, 2019.

As witnesses to the massacre and their families have faced attacks and some have been slain, there have been multiple delays and setbacks, and the majority of court appearances have been bail hearings. The Supreme Court granted Judge Joceyn Solis Reyes’ plea to delay the dissemination of the verdict by 30 days, or until December.

On December 19, 2019,Branch 221 of the Quezon City Regional Trial Court found 28 people guilty of murder, including masterminds Datu Andal Ampatuan Jr. and Zaldy Ampatuan, and sentenced them to reclusion perpetua or a maximum of 40 years in prison without the possibility of parole. Several others were found guilty of accessory counts and sentenced to prison terms ranging from 6 to 10 years. Around half of the defendants, largely police officers, were found not guilty.

The families’ struggle for justice is far from concluded, even with these convictions. All individuals accused of being involved in the massacre must be found and prosecuted by the government.

Political dynasties

With so much work needed to achieve full justice, the verdict to the so-called “trial of the decade” reveals deep-seated injustices in our country’s justice system. Political dynasties are one of the biggest exploiters of the unfair system to avoid punishment.

Such a case is evident when the largest political dynasty in the Philippines, Magundinao’s Ampatuan clan, can remain to enforce and create laws that they have violated in the first place. The nameless, ordinary Filipinos, such as the 32 media workers, are sidelined in the annals of history as mere collateral damage in the pursuit of power by elite families.

President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo has previously described the Ampatuans as valuable political friends, and many analysts have claimed that her support has empowered the clan.

In 2016, 26 Ampatuans ran in the elections, all of them related to the Ampatuan patriarch, former Maguindanao Gov. Andal Ampatuan Sr., who is among the suspects in the bloody Maguindanao Massacre.

What gave rise to the occurrence of the horrendous massacre is the Ampatuans’ insatiable thirst for power. Despite critics’ clamor, the political clan’s power remains at large in Maguindanao.

The Maguindanao Massacre created a spotlight on the foregoing political dynasties in the Philippines, hence highlighting the urgent need for an anti-political dynasty measure.

However, it is still a long way to go when the fate of legislation is in the hands of political dynasties in the Congress themselves who have no intentions to end their privileged positions of domination.

For many Filipinos, the trial is beyond proving a family’s guilt or innocence. It is about the Ampatuans’ enormous power and the culture of impunity that they wield to avoid accountability.

The Ampatuan case is only a glaring case of a common occurrence across regimes in the entire Philippine political history. In the upcoming 2022 elections, the Marcoses and Dutertes are no different. Political clans still remain as the Philippines’ worst nightmare, as they pose a larger fight for the country.

Journalist Killings

Attacks against the press are nothing new.

The Maguindanao Massacre did not only expose the disastrous clan and dynasty wars, but also the rampant killings of mass media workers and journalists in the Philippines

The case took a decade to come into a decision with proceedings protracted by over 400 witnesses presented by both sides and various procedural challenges including multiple death threats to the victims and assasination of at least 3 witnesses. The Committee to Protect Journalists’ (CPJ) Senior Southeast Asia representative said that the verdict for the Maguindanao Massacre will hopefully result in a “genuine break in the cycle of impunity in journalist killings in the Philippines.”

However, the trend has not changed. In 2018, the Philippines was tagged as the “deadliest peacetime country for journalists” due to multiple accounts of torture, killings, and kidnappings.

In 2021, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) recorded at least 21 journalists gunned down under the Duterte administration. Davao-based radio anchor Dondon Dinoy is the latest casualty.

Elite Privilege in Prison

While journalists face everyday dangers and threats to their work, imprisoned politicians are still the exception to the rule where justice is the rule.

Inside prison, the Ampatuans still enjoyed their lavish privileges. An Ampatuan was seen using a cellphone inside the jail and was free to walk in and out of detention based on photos and videos presented by Esmael Mangundadatu, spouse and relative of some victims of the massacre.

In August 2018, multiple clamors from the public hit the DOJ and Duterte administration as Zaldy Ampatuan was able to attend his daughter’s wedding at a posh hotel

This reality is far from political prisoners like Antonio Molina, who was denied of release as he battled Stage 4 stomach cancer; Reina Mae Nasino, who was only given half day to mourn her baby’s death; and Moreta Alegre, who was only allowed to attend for a two-hour furlough of her fellow prisoner husband’s funeral.

Privileges and VIP treatments for the elite and ruling class who are convicted are no news for the public. The unjust system that favors the rich and persecutes the poor shows how the elite can manipulate everything inside or outside the jail.

Where we are today

Until this day, political dynasties are still all over Philippine politics. In the upcoming 2022 elections, people from the same family and background are up against each other on the same government positions. Prominent families from different political dynasties are also lined up both in the local and national elections.

During Duterte’s bloody regime, the mass media, journalists and media workers, and press freedom are all under attack. Duterte was able to shut down and deny renewal of one of the biggest media companies, ABS-CBN, that acts as the primary source of news in the whole country.

The Duterte administration was also able to blacklist Rappler reporters from covering Malacañang Palace and initiated tax evasion and libel cases against its owner, Maria Ressa.

Alternative media workers are also under fire with continuous distributed denial of services (DDOS) attacks on press like Pinoy Weekly and Altermidya and the imprisonment of journalists like Lady Ann Salem, Frenchie Mae Cumpio, and Sham Astudillo, and red tagging of campus press.

With the recent and continuous attacks on press freedom, media workers are going through the same tortuous realities that they have been through during the Maguindanao Massacre. The burden of fighting and exposing the truth has been with them through the years.

Yet, media workers and journalists must remain truthful and brave while facing the potential danger in their field. There is an imperative to break free — break free from the culture of impunity and injustice that permits political dynasties to bury truths and journalists.

As we commemorate the Maguindanao Massacre, let this also be a reminder to continuously fight and call out the unjust system and a ruling Duterte regime that oppresses freedom of speech and silences their critics to remain in power.

#FightFor58

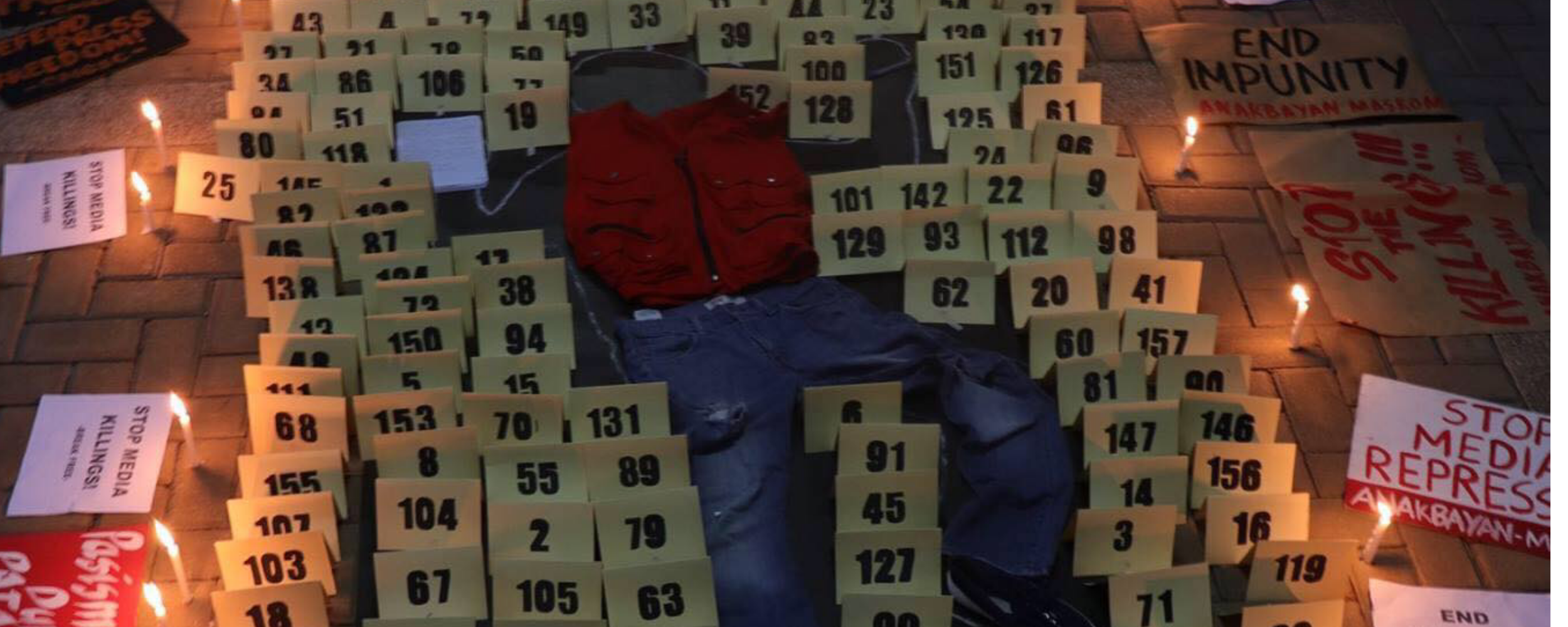

Featured image by SINAG

I’ve been searching for information like this for a while. I appreciate the detailed information shared here. The examples provided make it easy to understand. I’m bookmarking this for future reference. Thank you for breaking down complex concepts so clearly. This post is really informative and provides great insights!