Written by Kaya Novicio and Jam L.(co-creation with MODAMORPH)

There is undeniable tension between mainstream visibility and palatability versus the

counter queer culture—of drag art being a counternarrative to the shackles of polish, perfection, palatability, and sellability; thriving in fragments of transgressions and exaggerations and even performances that cause discomfort. Absurd. Sexual. Authentic.

The rise of mainstreamism in drag—which started out as both theatrical (e.g. Ancient Greek & Elizabethan eras) and underground (e.g. underground queer culture, ballroom culture, and gay bars) drag artistry and queer culture inevitably get bloated under consumerism, commodification; when it originally thrives in culture of tipping, of paying what you can, of non-commercialization.

Can it still retain the authentic radicalism, uncensorship, loudness, exaggeration that are at the core of drag? OR Does mainstream drag inadvertently promote a “homonormative” or “good queer” narrative that is palatable to the majority, hence neglecting or marginalizing the experiences of trans queens, drag kings, and queens of color, whose drag is often inherently more dangerous and radical and arguably more sacreligious?

But on the other side, we see its growth and potential in the stages of the industries of commodification—professionalization of drag, a bigger platform for political discourse even when sanitized to meet the standards of mainstream media and reputation. UNDENIABLY, it also inspires, say, the queer communities who needed that platform to amplify their own voices. Like Drag Race PH coming to life. Those are real.

But so are the questions on the illusion and commodification of queer culture. And so are the experiences after mainstreamismtook place.

The possible answer? Is to balance strategic use of the platform and the maintenance of a thriving non-televised scene which a lot of Drag Queens and Kings in the Philippines are already manifesting subversion from within, unsanitizing their respective narratives, bringing light to progressive ideals, creating their own spaces, supporting underground queer spaces; these are just some of the things that answered the questions purported above. But the longer problem is to sustaining it.How can we be sure that these subversions from the shackles of mainstreamism continue to derive and speak about discourses without falling to the same traps or being counterproductive themselves?

In an interview with Lulu Wang, Kaya Novicio writes that the discomfort, coupled with the problem of mainstream drag amplifies the very rebellion they ought to bring about even when there is a risk of palatability:

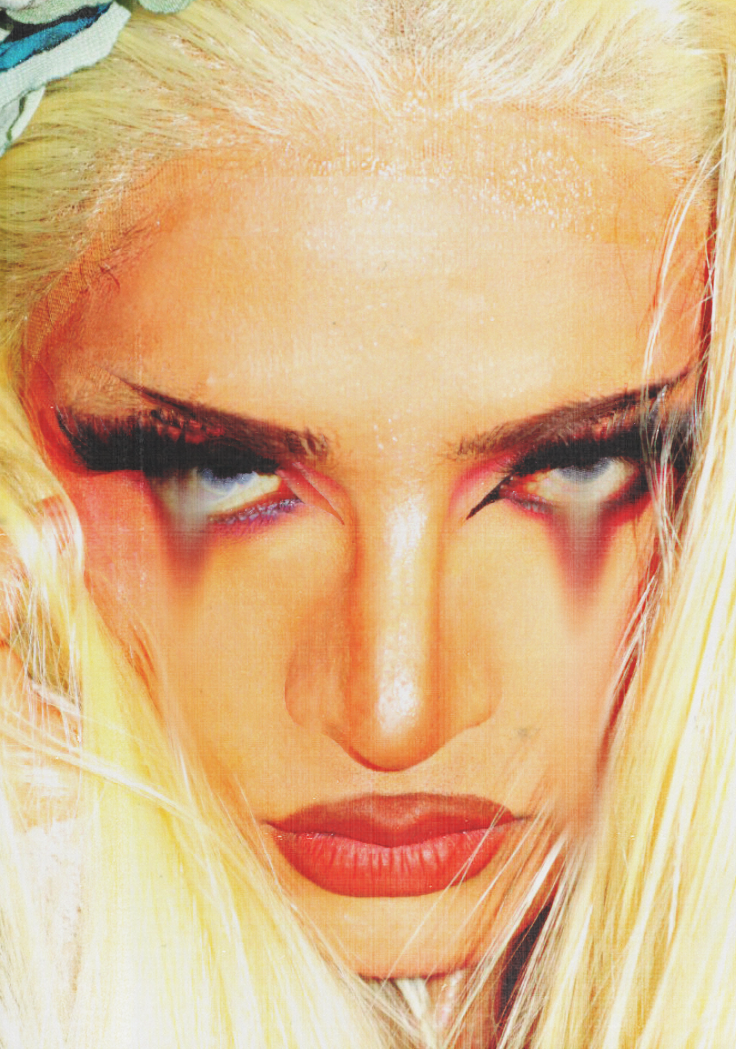

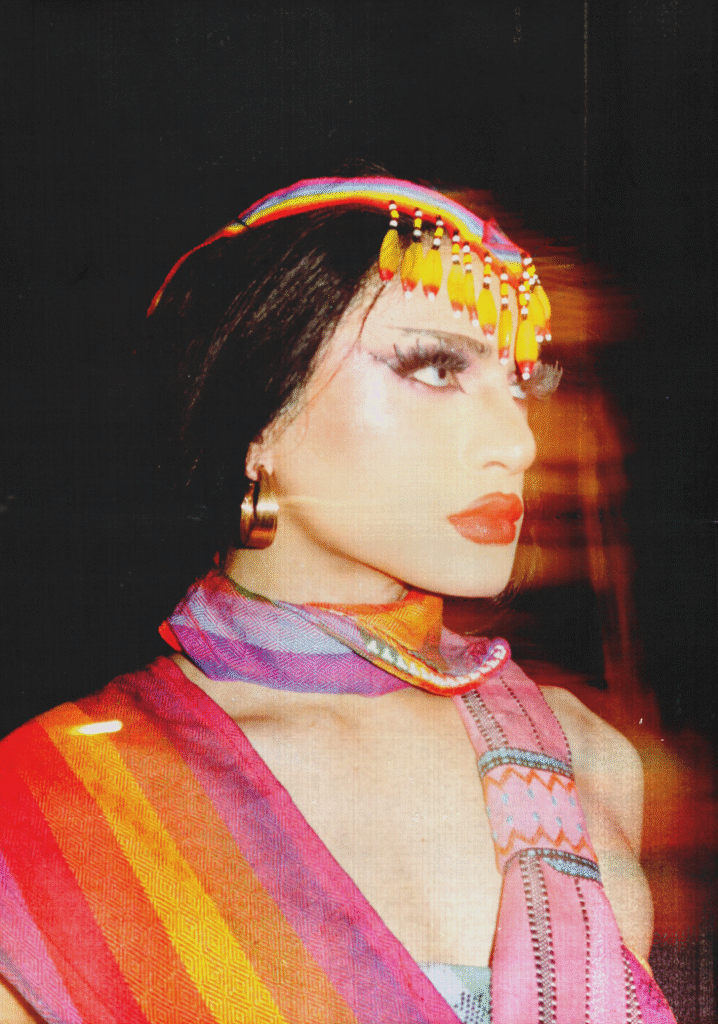

THE DRAG ARTIST’S BODY IS THEIR VOICE AND DRAG IS THE LANGUAGE

OF THEIR RESISTANCE AND REBELLION.

COVERING UP BECOMES THE DRAG QUEEN’S MEANS OF STRIPPING DOWN.

EVERY LAYER PUT ON IS ALSO A LAYER UNCOVERED. IT IS IN EXAGGERATION

THAT THESE ARTISTS MAKE VISIBLE WHAT THEY HAVE BEEN, FIRST AND

FOREMOST, TAUGHT TO SUPPRESS WITHIN THEMSELVES. THIS IS THE FIRST

LAYER OF VISIBILITY—THE FEMININE FIGURE THEY LET THE MIRROR SEE.

DRAG, LIKE MANY OTHER ART FORMS, IS A VEHICLE FOR BECOMING. IT IS

AN OUTLET FOR SELF-EXPRESSION; FOR SELF-DISCOVERY. “DRAG IS ANOTHER

VENUE FOR MY OTHER TRUE SELF,” FILIPINO DRAG DJ, LULU WANG, SHARED.

FOR HER, PARTS OF HER IDENTITY ARE SPACE-SENSITIVE, AND DRAG IS THAT

WHICH PROVIDES ROOM FOR HER EXTENDED SELF. “PAG NAGLAGAY NA AKO

NG LASHES, MAYRO’N SIYANG SIN’-SWITCH.” [WHENEVER I PUT ON FALSE

LASHES, SOMETHING WITHIN ME SWITCHES ON.]

THE QUEEN WEARS STILETTOS HIGHER THAN WHAT A COMMON LADY

WOULD WEAR, MAKEUP THAT IS FIVE LAYERS THICKER THAN WHAT A BEAUTY

QUEEN WOULD PUT ON, AND GOWNS LONGER THAN WHAT A GIRL WOULD SLIP

INTO ON A DAILY BASIS. FOR THIS, SOCIETY DEEMS THE QUEEN ‘TOO MUCH’.

THERE GOES ANOTHER LAYER OF—NOT QUITE VISIBILITY BUT—BEING

PERCEIVED.

DRESSED IN DISCOMFORT BEFORE THE VERY SOCIETY THAT FINDS THEIR

PRESENCE UNCOMFORTABLE, THE QUEEN FINDS FREEDOM.

“DRAG IS AN EXPRESSION OF REBELLION AND ANGER IN GLAMOR, IN

RHINESTONES, IN HIGHLIGHTERS, IN GLITTERS,” LULU WANG, SAID. “HINDI

LANG BASTA GLAMOR ANG DRAG; MAY KASAMA SIYANG ANGER. ANGER

COMES IN DIFFERENT FORMS,” [DRAG IS NOT A MERE PRESENTATION OF GLAMOR;

IT IS ALSO AN EXPRESSION OF ANGER. ANGER COMES IN DIFFERENT FORMS.] SHE

ADDED, EXPRESSING HER SENTIMENTS ABOUT DRAG’S POTENTIAL TO CONVEY

SOMETHING REBELLIOUS AND POLITICAL EVEN WHEN THE QUEEN IS NOT

PERFORMING FOR A STAGE NUMBER. POSING FOR A PHOTOGRAPH GOES

WITHOUT ZERO INTENT, BECAUSE AFTER ALL, IT IS STILL AN ACT OF PUTTING

ONE’S SELF ‘OUT THERE’. BEING SEEN THROUGH THE LENS OF A CAMERA

SUCCEEDS BEING SEEN BY EYES THAT AREN’T YOURS.

EVEN IN THE SILENCE OF A PHOTOGRAPH, THE DRAG ARTIST PROCLAIMS

AND ASSERTS THEIR SPACE.

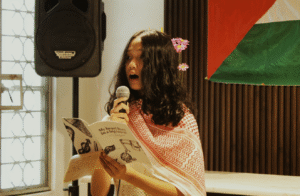

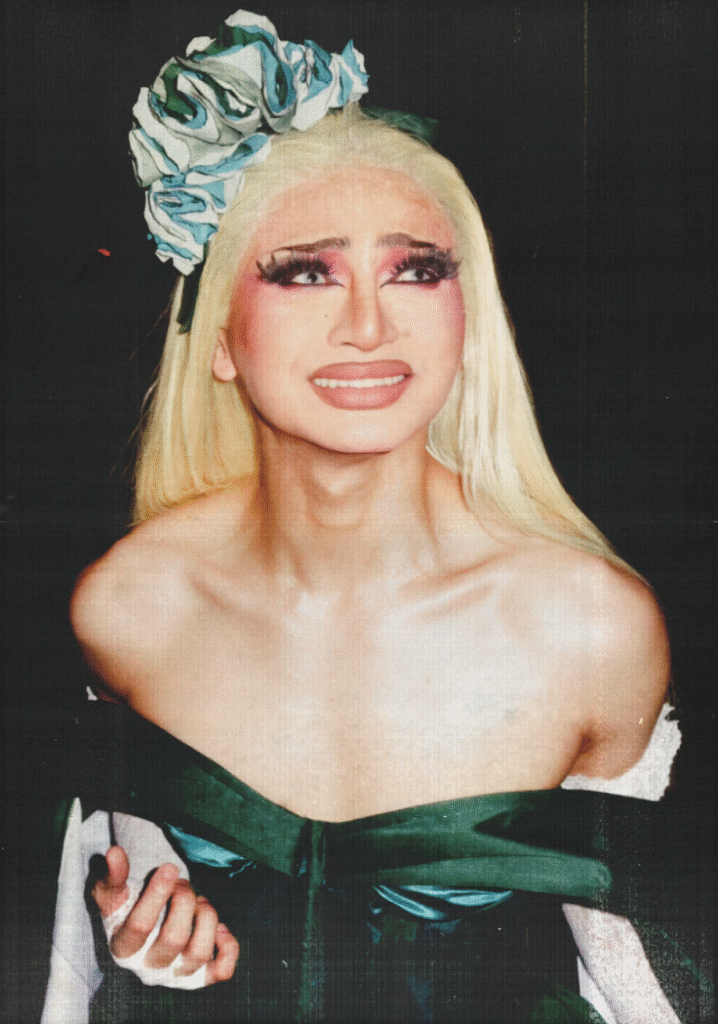

WHETHER THE DRAG ARTIST IS IN A SITUATION WHERE THEY ARE

REVERED OR WITNESSED BY A SINGLE PHOTOGRAPHER, BY SPECTATORS OF A

BARANGAY GAY PAGEANT, OR BY THE EXPOSURE FROM NATIONAL

TELEVISION—THERE IS ENGAGEMENT TO MAKE POSSIBLE THE ACT OF PUTTING

THEMSELVES ‘OUT THERE’. THE DRAG QUEEN’S POWER IS NOT CONTINGENT ON

THE QUANTITY OF THEIR AUDIENCE, OR ON THE BRIGHTNESS OF THE

SPOTLIGHT. TIME AND TIME AGAIN, IT HAS BEEN PROVEN THAT THE DRAG

COMMUNITY, GIVEN ANY CIRCUMSTANCE, MANAGES TO FIND THEIR

RESPECTIVE LIGHTS. TIME AND TIME AGAIN, THE DRAG ARTIST RESISTS THE

ERASURE OF THEIR IDENTITY, AND INSISTS VISIBILITY, MORE THAN MERE

PERCEPTION.

WITH THE PHILIPPINES’ LONG HISTORY OF COLONIZATION, THE QUEEN IS

THE RECLAMATION. SHE IS THE RECLAMATION OF THE NORM OF GENDER

FLUIDITY WHICH WAS APPARENT IN THE AGE OF THE BABAYLAN. SHE IS THE

MODERN-DAY TESTAMENT OF THE DICHOTOMY BETWEEN WHAT IT IS LIKE TO

CHALLENGE BEING EITHER A MAN OR A WOMAN. WITH THIS RECLAMATION

HOWEVER, DRAG FACES THE DILEMMAS THAT COME WITH GAINING

TRACTION—DOES DRAG BECOME CO-OPTED BY CAPITALISM AS IT REACHES

MAINSTREAM, OR DOES MAKING DRAG MAINSTREAM AMPLIFY THE VOICES OF

THESE ARTISTS?

With drag’s rise to mainstream, the exaggerated nature of drag becomes less of a necessity, as popular media platforms somewhat amplify the drag queen’s voice now. For instance, hit reality competition show, RuPaul’s Drag Race (RPDR) not only introduced drag to reality TV, but also actively provides opportunities for drag queens to showcase their art beyond the confines of their room, or their local drag scene. This phenomenon of drag going mainstream then raises inquiries regarding the genuineness of the art form. Do shows like RPDR reduce the value of these queens’ expression of identity to being mere commodities? Doesn’t RPDR slowly paint the public’s expectation of what a drag queen should be?

“Ang pagiging mainstream, hindi siya issue, progress siya,” [Drag going mainstream is a non-issue—it is a sign of progress.] according to Lulu Wang. For queens like her, drag goes beyond expression of their suppressed personal truths, for it is also a revelation of social realities that have been censored for the longest time. Having drag queens who are now brave enough to strip themselves down to display their extended self on mainstream media is the representation we have never seen before. With access to platforms as huge as RPDR, the drag queen does not have to do the most in order to be visible. Exaggeration is no longer necessary—drag is necessary.

It is necessary not only for defying the expectations entailed by being man or woman. It is crucial, because now, the queen also resists presuppositions surrounding what it looks like to be a drag queen. Now, they resist not only the rigid heteronormative system, they transcend binaries altogether. Going back to the radical origins of drag artistry in the underground scene, the alternative queen is on the rise, along with pageant queens, fashion queens—along with every other queen, really.

Together, they are angry. Together, they rebel.