A Commune, first and foremost, is a form of resistance. It is the manifestation of the emancipatory potential of the people to break free from the shackles of oppression and struggle for equality and democracy.

History teaches us that communes are sites of revolutionary militancy. Whether it’s the 1848 Paris Commune or the 1971 Diliman Commune, the mass movement has proven that the united peoples can liberate themselves by themselves and capture some form of authoritative power. Communes, just like what John Berger reminds us of mass demonstrations, are rehearsals for revolution; they are sites of utopian imagining, radical theory, and revolutionary practice.

February 1, 1971 saw the unity of the whole UP community to stand up against injustice. With the oil price hike amplifying a year of protests since the First Quarter Storm, students understood that UP should not be a sanctuary of the middle-class intellectual as the masses of farmers, workers, and urban poor suffered from recession and state fascism. The Diliman Commune is a nine-day uprising that became an evidence of UP’s role as the “bastion of activism” since the early days of the Marcos dictatorship.

The Commune is just a historical point in the long history of radical activism in UP. But the education institution itself – teaching Constantino’s nationalism, Sison’s national democracy, Marcos’s constitutional authoritarianism, or the Chicago Boys’ neoliberalism – did not cultivate activism in their students. Students had to learn it in the “university within the university” as Prof. Judy Taguiwalo calls it. This school teaches what textbooks cannot capture, the state education curriculum avoids, or the military censors erase or prohibit.

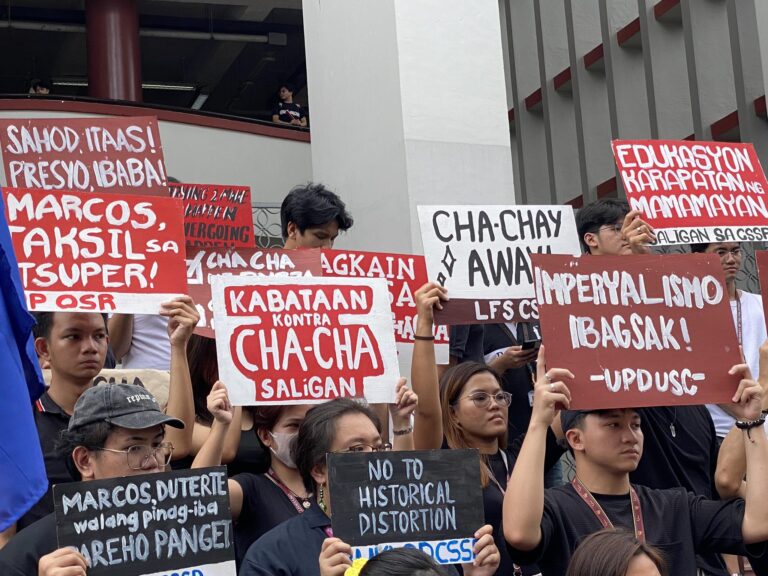

Certainly, in this said university, students knew that the struggle of landless farmers and exploited workers are real. And that genuine student power can only be attained by joining their forces and amplify their calls in the struggle, not for them, but with them. For them, imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat-capitalism are not just slogans but harsh social realities that have to be discussed and fought against. It was not Plato, Locke, or Weber who taught these lessons but the Filipino people to whom the “Iskolar ng Bayan” is indebted and vowed to serve.

As Amado Guerrero, the man who AS/Palma Hall was named after during the Diliman Commune, gives his timely reminder: “Only through militant struggle can the best in the youth emerge.”

Fifty years after, the spirit of Diliman Commune did not die. It continued to produce the likes of Lean Alejandro, Recca Monte, Tania Domingo, and many more who understood that UP’s liberation is futile if the masses are still in poverty and exploitation. The same fundamental problems remain and the “university within the university” withstood all state-sanctioned attacks. As long as social injustice remains, the specter of the Diliman Commune will haunt the ruthless barbarics who always reaffirmed to defend capital and crush the revolution – its theory and practice.

At a time when Marcos is being ressurected in another dictator, even worse than him, it is imperative for the whole community to raise high the barricades. But this time, it is not only a barricade to our university. It will be barricade to defend the people against fascism and state terrorism. We will break the barricades that divide us among our ranks and build our strong united front against our common enemies. The struggle will be long and hard but history also teaches us that no dictator stays in power forever.

Let us remember that the Diliman Commune was trigerred by an oil price hike against jeepney drivers. Today, the state is imposing a jeepney phaseout program amid a pandemic. This should open our eyes to the social realities that the masses are teaching us. Our present-day struggle calls for not only the defense of UP but to oust the tyrant Duterte. As the Terror Law resucitates the horrors of Martial Law, it will always be imperative to stand up and fight for our freedom, no matter what it takes.

To raise the barricades high at the time of a dictatorship is to militantly create history and rehearse for the inevitable people’s democratic revolution. Now more than ever, to raise the barricades high is the first step of our defensive on the long march forward to our offensive ouster campaign against a dictator. Barricades tell us what one wise philosopher said before: “Who are our friends? Who are our enemies?”

As the ever-strong chant goes, “makibaka, huwag matakot!” Today, let us arouse, organize, and mobilize to strongly raise the barricades high!

#DefendAcademicFreedom

#JunkTerrorLaw

#OustDuterteNow

______________

*Apologies to Philippine Collegian’s February 4, 1971 editorial during the time of the Diliman Commune

Artwork by Christine Garcia

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any tips on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Cheers