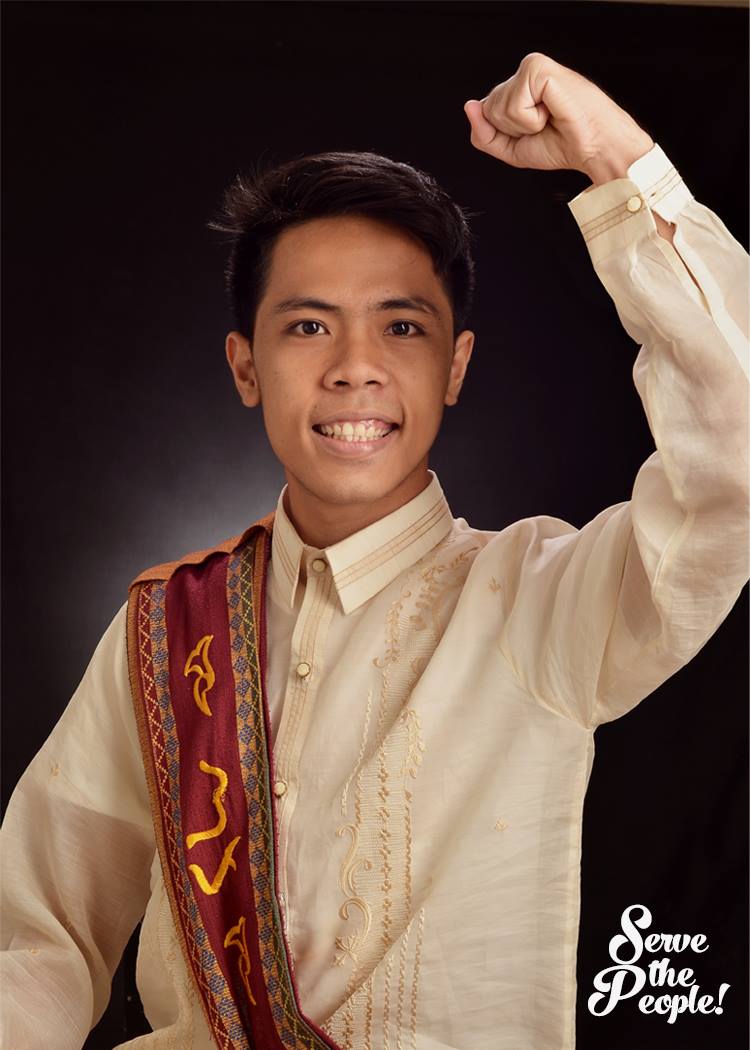

“Serve the people” is not just a recurring chant. For activists like Chad Booc, it is a lived reality.

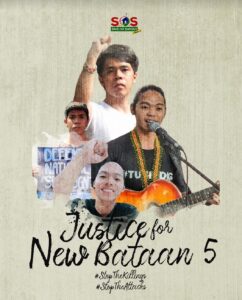

As the Supreme Court is set to resume the oral arguments on the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 (ATA) tomorrow, a combination of Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), police, military, and paramilitary Alamara elements raided the Lumad Bakwit School inside the University of San Carlos in Talamban, Cebu and arrested 25 individuals including Chad Booc – a volunteer teacher in ALCADEV Lumad School and a petitioner against the ATA.

No matter how the state spins the obvious truth, the Lumad 25 was arrested because of their endless struggle to defend their ancestral lands. For the longest time — even before the New People’s Army (NPA), which they are often linked to, was formed — the Lumad and many indigeneous Filipinos were already fighting development aggression, community militarization, and their right to self-determination. Attacks like what happened today is the state’s reaction.

Under President Duterte’s term, at least 136 Lumad schools have been shut down due to trumped-up allegations of “NPA recruitment”.” Today, state forces used the misleading narrative of “rescuing” the Lumad from progressive groups who supposedly “kidnapped” them to bring them into rallies. It is appalling that the state forgets that the reason why the Lumad people are evacuating is because its military and police are terrorizing them in their communities.

Back in 2017, Duterte himself even ordered the military to bomb Lumad communities while Martial Law was in effect in Mindanao. Bombing and militarization are everyday realities for the Lumad, prompting them to go to Lakbayan — a march of national minorities from the provinces to Manila to amplify their calls — and seek refuge in “sanctuaries” like UP Diliman.

It was during Lakbayan 2015 when Chad was enthused with the idea of being a Lumad school teacher and live a simple life in the mountains, according to a long-time kasama who described that event as an “eye-opener to centuries-old horrible conditions imposed by state terrorism and imperialist plunder”. In 2016, based on his Facebook post, he chose to go home with them in Mindanao. In 2017, he affirmed to dedicate his full time and energy in the struggle with them.

READ: https://r3.rappler.com/…/178032-up-graduate-answers…

He once wrote his “mula CS patungong CS” (from computer science to countryside) story, “Sobrang nabago ng mga kwento nila [Lumad] ang pananaw ko sa buhay. Talagang tumibay ang prinsipyo’t paninindigan ko.” (Their stories changed my views in life. My principles and beliefs grew stronger.) Chad did not decide and learn the simple answers from a GE class. It was the hardships of the Lumad struggle that taught him that there is more to the world than UP.

Chad had all the reasons to choose a high-paying corporate job and live a comfortable life after graduating cum laude with his BS Computer Science degree from UP Diliman’s College of Engineering. But social realities taught him more than his engineering courses. As a soft-spoken but dauntless national-democratic activist as he is, he knew that computer programs could wait until our society embraces a comprehensive program that is of the masses and for the masses.

But as long as the state criminalizes dissent and considers human rights defenders like Chad a rebel, or worse a “terrorist, the Lumad struggle continues. In 2017, Chad was among the Kabataan 8 who protested against the extension of Martial Law in Mindanao. They were arrested for shouting the calls of the masses, which put their trust in the Congress to represent them. It was a grim objective reality: justice does not exist for the oppressed and exploited!

The attack against Chad and the Lumad 25 is only a symptom of the systemic forced extinction of the Lumad people from their ancestral lands. The mining intrusion, militarization, and evacuation all points to a single problem: imperialist plunder. Our indigenous peoples are very vocal in defending their ancestral lands but state agencies and projects and their protected transnational companies like Dole, Del Monte, and Oceanagold drain our natural resources.

Sociologist Arnold Alamon wrote in his book, Wars of Extinction, that “[i]t was their economic struggles, however, as marginalized groups driven off and marginalized in their own land that struck me as the defining trait of the Lumad existence.” Extinction has become their life as economic, democratic, and cultural spaces narrow at the expense of so-called “modernization”.

This is why the government is a hypocrite to call today’s violence as a “rescue operation” when the people they were supposed to rescue retaliated and felt terrorized. It is the same logic they apply to legitimize state terrorism and red-tagging propagated by the bogus National Commission on Indigenous People (NCIP) — headed by ex-military men — their paramilitaries, and their network of fake datus and leaders who facilitate their intrusion in Lumad communities.

Due to Chad’s militant struggle with the Lumad to fend off state terrorism and imperialist plunder, he has been a constant victim of red-tagging and death threats. In 2017, he once posted a record of attacks related to his activism and said “blame the AFP for my death”.

SEE: https://tinyurl.com/53gdflpo

Four years later, Chad’s militancy did not waver as he stayed with his Lumad comrades who changed his worldview. The attacks and security issues kept coming but that did not stop him to amplify the voices that the state marginalized and silenced for a long time.

Along with fellow Lumad school teacher Rose Hayahay, Chad was among the petitioners who filed the 26th petition against the ATA. Indigenous peoples and Moros reject the law because, they say, it will only intensify state terrorism in their ancestral lands, especially in Mindanao, and facilitate the entry of transnational companies grabbing their “yutang kabilin” (ancestral domain).

Going back to Alamon, he proposes that the Lumad identity can only be reclaimed from misappropriation by considering it from a “class position”. The civil war is an actual experience for the Lumad people. But the Lumad struggle is not exclusive to the Lumad people. By viewing it in the vein of class struggle, it is an episode in the people’s history and life-and-death struggle against imperialism – the draining of our wealth by foreign capital to sell their surplus products in our markets — and fascism — the state’s open terroristic dictatorship to protect capital. Stuck in a warzone between armies of liberation and terrorism, hope in the struggle is all they have.

By accepting that the Lumad struggle is part of the class struggle, the state’s narrative that they will “rescue” the minorities must be rejected. As the revolutionary poet who once strolled the rich and lush Mindanaoan forests, Eman Lacaba, reminds us, “Awakened, the masses are the Messiah!” Chad and his struggle with the Lumad people is evidence that the struggle built on unities, and not divisiveness, lasts and accommodates room for more allies and supporters.

With the unilateral abrogation of the UP-DND Accord, the Lumad Bakwit School in their UP Diliman sanctuary is haunted by the specters of state terrorism they left in their homes.

Jaie Ramirez, chairperson of the local chapter of Chad’s political party in college, asserts that Chad’s arrest exposes that “hindi tayo ligtas sa panliligalig, pananakot, paghuli, at pagpatay” (we are not safe from trouble, threats, arrests, and killings) now that the Accord is gone. He claims that no Iskolar ng Bayan, and the Filipino people, is safe while Duterte is in power.

Ramirez adds that the youth have only two choices: first, to let the regime’s repression continue or second, we strip off Duterte and his allies the “right” to suppress us. Certainly, Chad and the story of the Lumad struggle teaches us that to struggle for a society where we are free is worthwhile and dignified. Only in a society where injustice is preserved are those seeking justice treated as criminals. If so, then to rebel is really justified if it means we change that society.

With his education, Chad channels the inner Marxist in him, “the point is to change” the world. But his education did not stop in the liberal University of the Philippines; it started to grow in the struggle within the ranks of the masses of farmers, workers, and national minorities. His story challenges us, the youth, “tumungo sa kanayunan, paglingkuran ang sambayanan” (go down to the countryside, serve the people) as each UP graduate is baptized after leaving the university.

Chad did not die today but the state’s attacks exposed the death of whatever semblance of a democracy we have and a moribund economic system whose grave we must keep digging. Following Chad’s life motto, “serve the people,” let me quote Mao Zedong. “All men must die, but death can vary in its significance. To die for the people is weightier than a mountain, but to work for the fascists and die for the exploiters and oppressors is lighter than a feather.”

Chad could have worked in a large transnational company but he chose to serve the people.

Featured image courtesy of Chad Booc.