In a 135-page ruling signed on Wednesday, September 21, the Manila Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 19, under presiding judge Marlo Magdoza-Malagar, dismissed the Petition, filed by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2018, that sought to declare the Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) as “terrorists.”

Judging based on the repealed Human Security Act of 2007, the court noted that the violent acts committed by the CPP-NPA merely qualify as “rebellion” and not “terrorism,”.

Accordingly, Magdoza-Malagar ruled, that the CPP-NPA can only be rightly tagged as a “rebel” organization and not as a “terrorist” group because it does not see violence as an end but a means to achieve its goals outlined in its Party program.

DOJ’s petition

The Petition was filed by the DOJ through Deputy State Prosecutor Peter L. Ong, who is also the chairman of the Task Force on Counter-Terrorism Including Terrorism Financing and Local Insurgencies.

The first Petition was filed on 21 February 2018 and amended twice on 03 January 2019 and 14 June 2019, during the Duterte administration.

The Petition implicated the CPP-NPA to be declared a “terrorist” organization due to the following allegations:

1. That the ideology of the CPP-NPA sanction violence as a means to achieve their goal of overthrowing the duly-constituted authorities or the government;

2. That an internal split in the CPP-NPA in the 1980s has led to a faction which employs atrocities that have caused deaths to their very own members;

3. That the CPP-NPA have committed atrocities against innocent civilians; and,

4. That the CPP-NPA have committed atrocities against police and military personnel.

The Petition further insisted some atrocities as “terror” acts allegedly committed by the revolutionaryl organizations. These include internal purges, atrocities against civilians, and attacks against military personnel.

Court’s decision

The Court examined the CPP-NPA to discern if it qualifies as a terrorist or not, thus concluding the following:

1. Evident in its structured and nationwide membership, CPP-NPA is unquestionably an “organization.” The decision defines an “organization” as “a group of people with a definitive purpose, with clearly defined roles and responsibilities.” Whereas, an “association,” which the CPP-NPA is not, is mere “an informal group of people sharing similar interests.”

2. Section 3 of the Human Security Act (HSA) of 2007 defines “terrorism” as “the commission of any of the acts enumerated there under…thereby sowing and creating a condition of widespread and extraordinary fear and panic among the populace, to coerce the government to give in to an unlawful demand.” The decision then asked if the “purpose” of the CPP-NPA’s conception was to engage in “terrorism” as the HSA 2007 defines it.

After referring to the constitution of the CPP, which laid out the purpose of the organization, the decision concluded, “while ‘armed struggle’ with the ‘violence’ that necessarily accompanies it, is indubitably the approved ‘means’ to achieve the CPP-NPA’s purpose, ‘means,’ is not synonymous with ‘purpose.’ Stated otherwise, ‘armed struggle is only a ‘means’ to achieve the CPP’s purpose; it is not the ‘purpose’ of the creation of the CPP.”

Simply put, the court debunked false claims of rebellion or the armed struggle as terrorism, firmly concluding that revolutionary violence is a “means,” to achieve the CPP-NPA’s program, and not the organization’s goal.

3. The decision assessed nine incidents of “terrorist acts” allegedly by the CPP-NPA. Based solely on eyewitness accounts, they appear to constitute crimes defined under the Revised Penal Code and Other Special Penal Laws and enumerated in Section 3 of HSA 2003 as comprising terrorism.

However, the Court noted that the eyewitnesses merely identified the alleged CPP-NPA rebels, who allegedly committed the nine “terrorist acts,” primarily by all-black clothing.

“This identification leaves much to be desired. Certainly, it takes more than a certain manner or mode of dressing to establish that one is a member of the CPP-NPA. In the absence of any evidence that the official uniform of the members of the CPP-NPA consists of an all-black outfit, this Court cannot give credence to the witnesses’ identification,” the Court concluded at the lack of convincing pieces of evidence.

4. Another element of “terrorism” is the “acts are committed to sow and create a condition of widespread and extraordinary fear and panic among the populace.” However, the Court noted that the terms “widespread” and “extraordinary” are vague.

“[I]n determining whether or not the panic and fear are ‘widespread’ and ‘extraordinary,’ the Court will apply these qualifiers within the context of the Filipino ‘population,’” the decision clarified.

Accordingly, the Court decided that the aforementioned nine incidents cannot be considered “terrorist acts” since they are not “widespread” and “extraordinary,” as legally defined.

5. The Court further underscored that the enumerated nine atrocities were not “widespread” and “extraordinary” enough to be considered “terrorist acts” because of CPP-NPA’s chosen battle strategy which is guerilla (“little war”) warfare.

Accordingly, “guerilla” is not synonymous with “terrorism,” since “terrorism” constitutes more extensive and remarkable organized violence against the Filipino population and not merely sporadic acts of violence with no specified victims or targets.

6. Another element that constitutes terrorism is the acts “committed to coerce the government to give in to an unlawful demand.” However, the Court concluded that such an element does not apply to CPP-NPA due to two reasons.

First, the nine alleged atrocities are not “widespread” and “extraordinary” enough, as previously expounded, for the government to be coerced.

Second, the DOJ failed to show that the objectives of the CPP-NPA, as defined in its constitution, as constituting “unlawful demand.”

CPP-NPA’s demands are suitably rooted in Communist ideology, which to believe therein or in any ideology is legal in the country and protected by human rights.

Accordingly, the CPP-NPA, and its guerilla, cannot coerce the government enough to provide even any demands, much less unlawful demands.

With these, the Court ruled that the CPP-NPA cannot be referred to as “terrorist,” thus dismissing DOJ’s Petition.

Dissent and armed struggle are rooted in persisting socio-political ills

The decision emphasized, “[r]ebellion is rooted in a discontent of the existing order which is perceived to be unjust and inequitable to the majority, and favourable to the wealthy, ruling few. Rebels are usually compelled to resort to violence simply for lack of avenues to be heard, and in order to be in a position to significantly change the status quo.”

READ: http://bitly.ws/uwUK

The Court advises the Philippine government that the efficient and just manner to address and resolve armed rebellion is by addressing the root issues, essentially stating that militaristic and reactionary responses are futile.

The decision further asserted, even in facing armed dissent, the government must employ counter-insurgent measures with respect for the right to dissent, due process, and the rule of law.

The Court underscored that people join and remain affiliated with the CPP-NPA, and any rebel organizations, due to righteous indignation engendered by unjust conditions in labor, land, and anti-people status quo.

They reiterate the necessity for the state to address the aforementioned root causes of dissent to resolve armed conflict.

“Indeed, measures that seek to include conflict management and post-conflict peace-building, addressing the roots of conflict by building state capacity and promoting equitable economic development will hopefully stamp out ‘terrorism’ and eradicate its seed,” the Court ruling added.

Despite such ruling, the Justice Department said that they will re-file another similar case against the CPP-NPA on the basis of the draconian Anti-Terrorism Act of 2022.

Meanwhile, the CPP welcomed the decision as “reasonable and fair” and highlighted the fact that the CPP-NPA is not a terrorist organization but one that has political aims such as building national industries, land redistribution, and national sovereignty which can aid legal activists in pushing back against red-tagging.

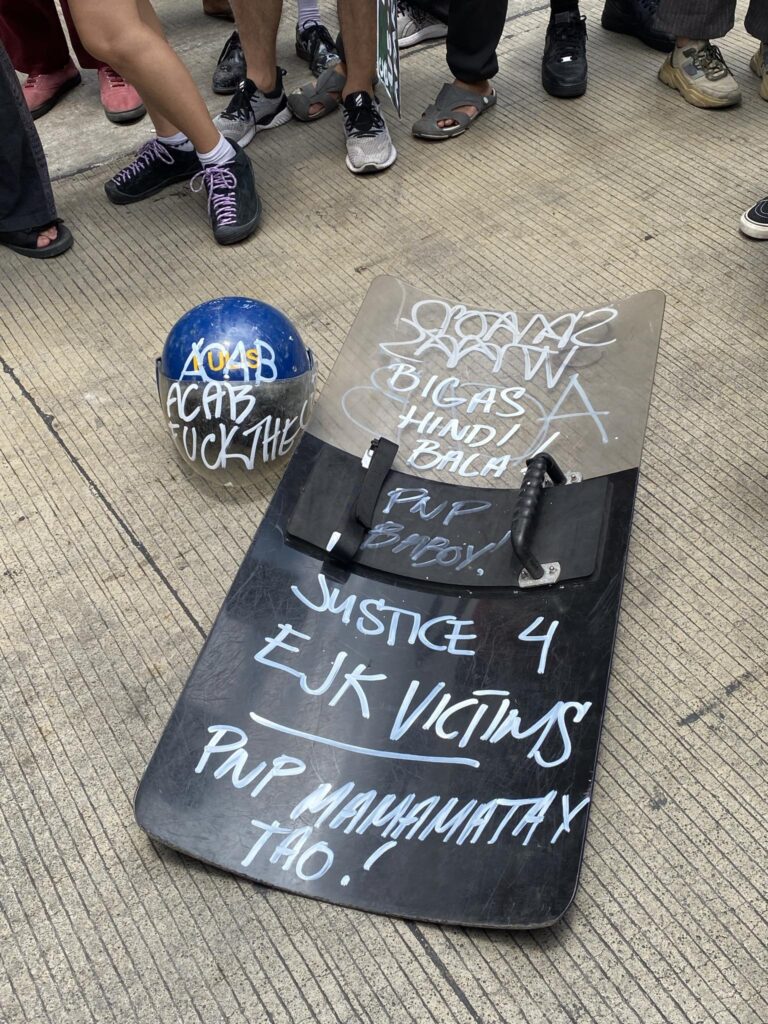

Featured image courtesy of Rappler

You helped me a lot by posting this article and I love what I’m learning. http://www.hairstylesvip.com