The UP Diliman College of Social Sciences and Philosophy Student Council (UPD CSSP SC), together with the UP Diliman College of Mass Communication Student Council (UPD CMC SC), proposed “a resolution calling for intensified efforts and campaigns for a more inclusive university especially for disabled stakeholders,” which was adopted during the second day of the 53rd General Assembly of Student Councils (GASC) on August 27, Saturday.

READ: http://bitly.ws/tLQJ

A long struggle towards inclusivity

Despite constituting 15% of the world population, disabled people have long been marginalized, despite a supposed “accessible” education in the country.

Within and outside the University of the Philippines, however, the neoliberal status quo of Philippine education sees no market-oriented utility to provide better conditions for those excluded from the world designed for “abled bodies.”

And in the times when such concerns resist emerging, the response is mere tokenism—underutilized provisions that appear destined to remain on paper.

The resolution noted that the Philippines is a signatory of the United Nations Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities since 2008; the Accessibility Law, which aims to accommodate disabled people with inclusive establishments and other services, was signed in 1983; more laws were passed, including Republic Act (RA) No. 7277 and later amended by RA 9442, RA 10754, and RA 11228, to further the necessary rights such as VAT exemptions and mandatory PhilHealth coverage; and through Presidential Decree No. 1509, the National Council for Disability Affairs (NCDA) was established.

Nonetheless, “deriving from the lack of budget for both education and disability, accessibility implementations remain lacking in Philippine education, leading to institutions which largely other disabled students and limit integrative intervention,” the resolution lamented.

Earlier, the Commission on Audit (COA) flagged the Department of Education (DepEd) due to P4.527 million worth of deficiencies in the use of the budget intended for the Basic Education-Learning Continuity Plan (BE-LCP) for school years 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 despite the ongoing educational crisis amid the pandemic.

READ: http://bitly.ws/tLQS

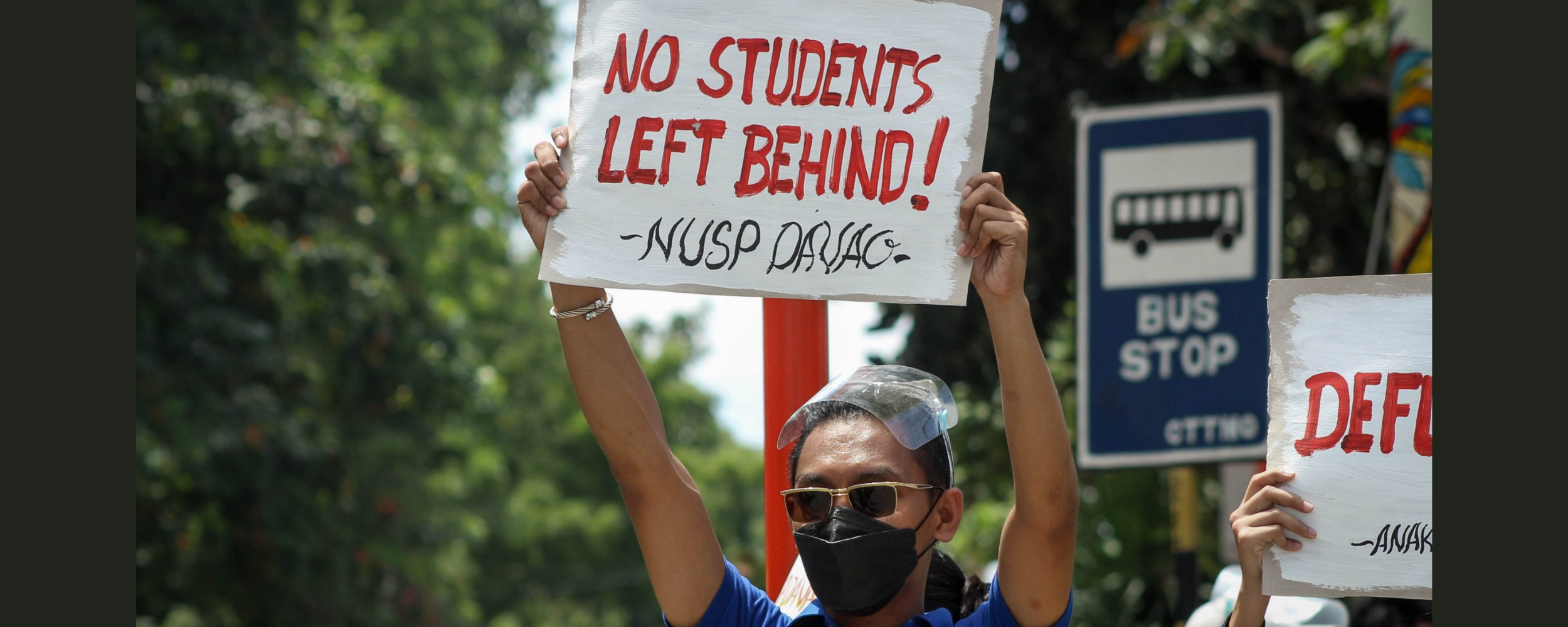

Amid the issue of corruption, DepEd promised that “no student will be left behind.” However disabled students are continually excluded from the discourses on developing programs and services for students during remote learning.

READ: http://bitly.ws/tMAT

Moreover, the university is facing more-than-half worth of cuts in its proposed budget for FY 2023. Of the proposed P44.149B, only P21.854B will be allocated to the university. This, will the Office of the President will receive an initially non-deliberated P9B worth of funds—the majority of which is to be distributed for the use of national security.

The Polytechnic University of the Philippines, the largest public university by population in the country with over 70,000 students, is also threatened with a P129 million budget cut for 2023 by the DBM.

READ: http://bitly.ws/tEBQ

With the continuous cutback on the right to free accessible quality education, “inclusive education accommodations remain insufficient to fulfill the additional needs of disabled students, especially in institutions where space is shared between those with and without disabilities,” the resolution noted.

What it means to be disabled

In a debate among student councils regarding the said resolution during the assembly, a search for the right term ensued. Is it “disabled,” “with special needs,” “people with additional needs,” or others?

One of the authors from UPD CSSP SC contended, “[w]hen I’m disabled, my needs are not special. They’re just needs. I don’t want someone to call me a person with disabilities, I want someone to know I am disabled.”

UPD CSSP SC Chair Vayne Altapascine del Rosario argued that a social approach by disabled people themselves, rather than a medical approach, should be used.

“[B]y using the term ‘disabled,’ we want to create something new…Every single thing that I experience is colored by disability. We cannot separate the person and the disability…We don’t want others to speak for us. We talk for ourselves,” del Rosario asserted.

Hence, the body adopted the term “disabled stakeholder.”

This reveals the thorough nature of disabilities—that the concept of disabilities must not be locked inside the medical echo chamber.

To be disabled is a lived experience caused not merely by physiological characteristics but especially by how society, and how it is insisted to be designed, responds to its disabled members.

In other words, a disabled person, for instance, in the domain of mobility is not so merely due to one’s physical impairment, but rather, due to a lack of usable ramps, elevators, and other necessary accommodating building designs.

The resolution suitably underscored the socio-political background of disabilities.

“[T]he colonial, commercialized, and anti-democratic orientation of the [Philippine education] remains a means by which systemic shortcomings are put into force, especially imposed by over-bureaucratization of definitions of disability, funding restraints on research items especially involving disability, and the slow institutionalization of important offices related to the [Philippine education],” the resolution stated.

Disabling the disabled

The University, a supposed school for the masses, exhibits the same problem, having been flagged by the COA in 2011 for non-compliance with the national expenditure’s 1% allotment for projects for PWDs and senior citizens.

Although there have been some leaps toward inclusivity, for instance through UP Diliman Health Service’s Students With Additional Needs (SWANS) program, they are nonetheless underdeveloped, evidenced by the lack of assorted accommodations; underfunded, evidenced by the lack of resources; and underpublicized, evidenced by the lack of benefiting students.

Likewise, the system-wide Student Wellness Subsidy Program is also underutilized due to similar reasons.

It should also be noted, as did the resolution, that some mental health conditions can be debilitating or other disabilities, especially in the University insufficient of necessary services for its disabled stakeholders, can induce mental health problems, which can also be further debilitating.

The Philippine Collegian earlier reported that UP Diliman PsycServ, currently a “special project” under the chancellor’s office that aims to mitigate the mental health needs of the UP Diliman constituents, is struggling with inundated service requests amid the lack of resources.

READ: http://bitly.ws/tMAt

The article noted that many, if not most, mental health grievances are due to the pandemic and the current remote setup.

The resolution also underlined, “in light of the pandemic, difficulties from disability have been exacerbated by the University’s exclusively remote learning policies, uneven implementations of compassionate academic policy, and often-limited or late dissemination of health policy.”

READ: http://bitly.ws/tPQG

The issue of mental health is also addressed in a separate adopted resolution, also authored by the UPD CSSP SC among other councils.

The unceasing clamor for visibility

Accordingly, it is no question that the University’s earlier efforts remain insufficient. As the representatives of the student body, the General Assembly thus resolved to:

• campaign for greater funding allocation for inclusivity and accessibility efforts on UP campuses, especially for those pertaining to UP’s development plans and the comprehensive review of educational curricula and academic policies;

• amplify voices of disabled stakeholders, their campaigns, and their organizations, especially in relation to topics on disability, to build in equity the capacity for mass education on disability, accommodation, and community-building;

• call for the junking of the Master Development Plan and all other corollary neoliberal development plans and, in their stead, push for community-based, consultative, and pro-people development within and outside the University;�

• call for the provision of inclusive designs of buildings and classrooms that will cater to the particular physical necessities of disabled individuals;

• continue and strengthen academic ease policies, in solidarity with disabled students whose optimal conduct of education has been greatly compromised by the pandemic and limited allowances of face-to-face learning;

• call for streamlined response mechanisms among faculty and staff in addressing SWANS concerns, such that those in need of specialized assistance are most swiftly able to receive appropriate relief;

• adopt the call to make available inclusive options for modes of learning, including those of flexible conduct such as online and blended classes, as well as non-standard means of learning delivery;

• lobby for accelerated expansion and increased budget for programs such as the Student Wellness Subsidy Program intended to provide basic aid for the fulfillment of accommodation and medical necessities;

• commit to campaigning for the establishment of disability consultation and research projects similar to Total Inclusive Environment in UP Diliman for other constituent units in the System;

• intensify campaigns for the institutionalization of PsycServ, the establishment of similar initiatives, and the provision of accessible, comprehensive mental health services across the UP system; and

• uncompromisingly defend the right of University stakeholders to equal access to its facilities & services, in order to uphold a University for the People from which progress leaves no one behind.

Despite the marginalizing status quo, the General Assembly continues to stand with its disabled constituents in their fight for their inherent rights.

UPD CSSP SC Chair del Rosario clamored, “…members across UP campuses deserve to be here, have a right to space here, and we leave none of them behind.”

#GASC53

Featured image courtesy of Sofia Roena Guan