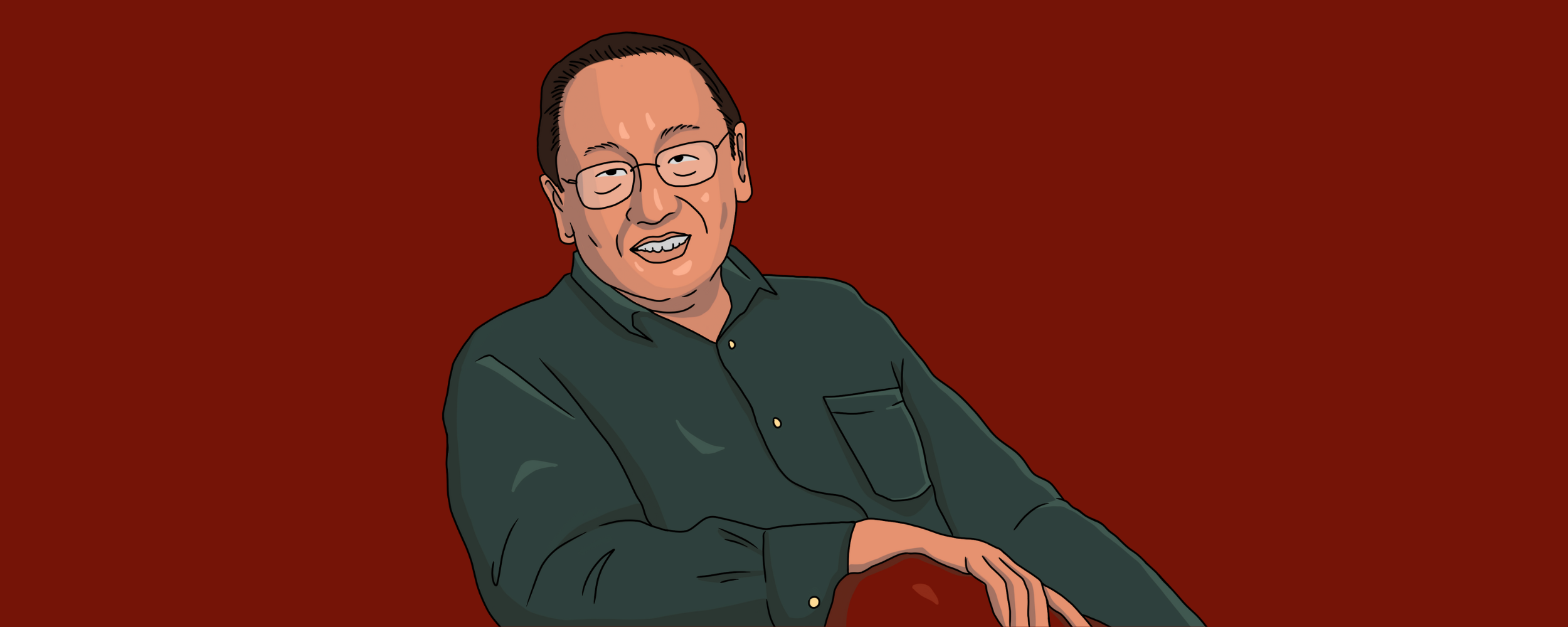

It was once said that the guerilla is a poet. But an often untold story is of the guerilla who is a social scientist. The life and martyrdom of Jose Maria Sison tell both stories, offering a rich literature on how to make social sciences serve the struggle of the people for liberation.

Contradictions in objectivity and partisanship

Lenin wrote that in a society divided into contending classes, there is no “impartial social science.” Scholarship, in this sense, is already a partisan deployed in the terrain of class war.

Sison’s extensive body of writings in the 1960s served as pillars of a living revolutionary movement that continues to understand the world as it constantly attempts to change it –revolutionary practice heavily rooted in revolutionary theory. As Lenin once said, “without revolutionary theory, there can be no revolutionary movement.”

The tradition of the social sciences stems from a history written from the academic ivory towers. Since the time of Plato until Joseph Scalice, the social sciences have been co-opted to serve the intellectual needs and moral excuses of anti-people policies of the State. On the contrary, alternative currents in the social sciences, especially the Marxist tradition, attempted to steer the field into a more progressive direction. This struggle for meaning and purpose reflects the contending notions of objectivity in the social sciences.

For conservative social scientists, objectivity means being above society. While they are compelled to reject certain biases, they still uphold ones that tend to preserve the status quo. In the end, a so-called objective social science is produced from the detachment to the realities and language of the masses by intellectualizing and obscuring their suffering through jargons and concepts that are often divorced from everyday realities.

But radicals like Sison propose another definition drawn out from their social practice. For them, objectivity is not being above society but being within it. Through a partisan revolution and education, the diagnosis and prescription of social ills and their roots become objective in themselves. As Neferti Tadiar says, an objective revolutionary social scientist learns to speak with the masses before speaking for them. These two opposing notions of objectivity raise the question of the role and extent of partisanship in objective research.

Now, is there room for partisanship in social sciences that prides itself to be objective? We can see that objectivity, whichever camp deploys it, is already partisan. The assumptions of the Government in railroading the Maharlika Wealth Fund and the Mandatory ROTC as they justify their social benefit already favor a certain group. In the same vein, the revolutionary program for land reform and armed struggle of communist rebels also favor certain classes.

Thus, it becomes futile to debate if social science can be partisan or not. The more pressing and relevant debate today is: for whom does this partisanship-cum-objectivity serve?

A social science serving the people

Sison is partisan for the people, analyzing the roots of our underdevelopment in his 60-year corpus of works. By making social science serve Filipinos, Sison has also served the development of Filipino social science. Writing extensive interventions on Philippine society, he has produced some of the most straightforward yet sharpest and durable analysis of it.

Owing to his time as a guerilla and an ardent student of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, Sison’s social science research program is informed by the Philippine revolution’s theory and practice to liberate the Filipino people from the shackles of semicolonialism and semifeudalism. His creative application of Marxist theory to Philippine reality shaped the country’s history and politics in the last 50 years. The result of his intellectual leadership and ideological theorizing is what Dominique Caouette calls the “persevering revolutionaries,” especially at a time when revolution seems to be marginalized by the State’s hegemony.

Being one of the most brilliant theoreticians of the Philippine Left, Sison also shaped the history of communist theory and practice in the country and the world. He must be credited for his seminal work, the Philippine Society Revolution, that laid the movement’s basic analysis and language. “Mayaman ang Pilipinas ngunit naghihirap ang sambayanang Pilipino,” will always be a baptism of fire for thousands of activists who dream of change.

In other fields of study, he wrote, often with his wife and comrade Ka Julie, about political economy and its “semicolonial and semifeudal mode of production” in the Philippine Economy and Politics, about politics in the Anatomy of Philippine Politics and Social Basis of a Fascist State, about geography in the Specific Characteristics of our People’s War, about sociology in Our Urgent Tasksand the US Cultural Imperialism in the Philippines,and about different fields in thousands of interviews he gave. His collection of writings, the legacy he leaves to the next generations of revolutionaries, is memorialized in the 30-volume Sison Reader Series. With such intellectual rigor, Sison has contributed so much in the Filipino social science, despite being constantly marginalized in university spaces and curricula.

The distinctiveness of Sison’s social science is marked by three main elements. First, the artistic, yet creative, presentation of his ideas invites readers to think about social issues in ways that diverge from conventional thinking. Second, as Myfel Paluga posits, his seemingly “formulaic statements” are in fact durable formulations that serve as practical guides in the revolutionary schools of armed struggle. Third, combining his artistic creativity and durable social scientific outlook, Sison applies the social science in studying society outside the academe by making the study of society a practical task that the oppressed must undertake.

Some Prospects for Filipino Marxism

A number of academic books have been written by scholars on the state of Marxism in the Philippines. Various eulogies to Sison appraised his theoretical legacy differently. Like his challenge 30 years ago, some say it has to be reaffirmed while others say it has to be rejected. Despite contending assessments of Sison’s contribution to Filipino social science and Marxist theory, it is indisputable that Sison is one of the greatest Filipino social scientists of the last decade as he accepted Marx’s challenge of not only interpreting the world but also changing it. He proved that studying society is and should not be confined to the university.

When revolutionaries die, the movement keeps its optimism by saying that the revolution will carry on. Sison’s death is indeed an end of an era. But his death poses both challenges and opportunities for the Philippine Left to gain more political power in an elite-ruled regime we have (or the bureaucrat-capitalist state, in Maoist language). Sison’s life may have ended but the greatest product of his ideas, the national democratic revolution, has not come to an end.

For Maoists, their future is theirs to make as they continue their revolution without Sison. For other Left formations who are critical of Sison since the 1990s, the challenge for them is to at least create comprehensive critiques of the Philippine society and revolution and build real mass movements that effectively challenge the hegemonic rule of the reactionary state. In essence, it is the continuing political struggle that will dictate the future of Filipino Marxism.

Sison’s death does not mean the end of the Philippine revolution and Marxism. The very same phenomena he analyzed in the 1960s—foreign domination, landlessness and industry-lessness of the masses, and elites running the government—still define Philippine society. Yet, the revolution he started in 1969 is still being nurtured by the fertile grounds of crisis. Its victory, as the late Fidel Agcaoili said, “will come” no matter how long it takes.

Today, social science students have a lot to learn from Sison and his social scientific research project. With another Marcos in power, we must remember that Sison’s ideas mobilized nationalist youth in the Palma Hall during the Diliman Commune until they went to the countryside to study society from the perspective of the masses outside the campus.

The prospect for Filipino Marxism thus relies on the direction of Philippine revolution post-Joma. Revolution is indeed a historical inevitability and necessity carried out by the masses who create their history. The prospect for Filipino Marxism thus relies on the future of Philippine revolution post-Joma. To paraphrase Sison, it is in this militant struggle that the best in the society will emerge. Even without its founder, the revolution will persevere.

For as long as the guerilla is a social scientist, the revolution will certainly not just interpret the world; it will transform it as well.

#KaJomaLives

Artwork by Kiko Buenaventura